Day 1: Draw a Bicycle (and sketch a key mechanism)

This is a warm-up exercise. As warm-up exercises go, what are we warming up for? A daily practice of noticing (what we don't notice, too). Of using a journal to probe deeper. A daily practice of doing just enough, just good enough to learn something (we're aiming to keep this to around 15-20 minutes a day). Where we will use different perceptual and conceptual tools, and follow prompts that are open (so ambiguous) enough that people in very different contexts can do something meaningful.

If you've done the "draw a bicycle" exercise before: skip step 1, and go to step 2, so that you can get to step 3 (it's new) and 4.

If you're new to this, do steps 1 and 2, and 4, and step 3 if you have time.

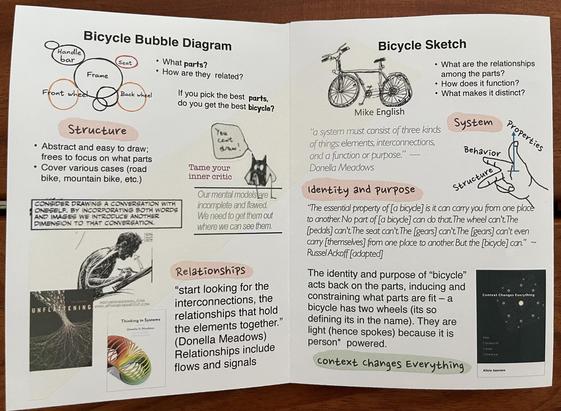

- Draw a Bubble Diagram of a bicycle. Use labelled bubbles (circles) to express the key concepts of a bicycle; use placement and size to convey relationships. [There's an example of a Bubble Diagram in the image above.]

- Sketch a bicycle from memory. (Don't look at a bicycle or picture of one, just go ahead and sketch it.)

- Pick a key capability or function of a bicycle, like steering, braking, moving, ... Use sketches and words to explore and convey how it works. (e.g., if you picked steering, what parts are involved and how do they work, to enable going in the intended direction.)

- Reflect on what you learned. What do you notice (more)? Jot down some notes/observations about drawing to see, to think, ... And jot notes on what we learn about systems, and our observing and making sense of systems we encounter. And perhaps even interact closely with.

At the end of Day 1, we'll add some notes and link to some of the work folk have shared on Mastodon, Bluesky or LinkedIn.

'Drawing [isn’t] just for “artists” [..]. Think of it as a way of observing the world and learning' — Anne Quito

Discussion

Spoilers ahead, so save reading this section until after you have completed this exercise.

Here are some of the wonderful drawings and reflections that our fellow Adventurers have so generously shared:

The shared work is a wonderful contribution to the community experience! I'd like to quote Sebastian Hans' reflections. (For context, Sebastian did this exercise last Advent too.)

"What I noticed (step 4):

- I paid more attention to how the parts were connected this time around.

- Drawing made me notice I don't know the exact angles between parts of the frame. My drawing looks slightly skewed.

- I see what I didn't draw.

- Just because you interact with a system often this doesn't mean you understand it.

- There's always another layer. I did note the necessity of friction, but I didn't describe how this comes about (gravity, usually).

- The system only works at all in connection with its environment. Without the ground, the bicycle doesn't move."

We might assume we have a pretty good notion of what a bike is composed of, but when we need to draw the actual relationships among the parts, our knowledge of those relationships, generally speaking, is more fuzzy than we might have expected. When we look at our drawings and start to probe how they work, we might realize we missed something, or got the realtionships wrong enough, that it could not work as drawn. Sure, if we ride a lot, and maintain our own bikes, we have more of a sense of the structure and key relationships and essential parts than if we don’t. But even then, it’s surprising to a lot of daily cyclists, that there are various relationships among structures and mechanisms they aren’t really that sure about when they come to draw a bicycle.

Our brains are pretty amazing. They conserve. We don't notice and remember everything we encounter, because that's inefficient most of the time. Without even realizing it, we rely on the world to hold information we don't need:

“The world is its own memory.” — Kevin O’Regan

Still, our mental models are incomplete, and we aren't generally aware of this until we really engage with them, and surface where we have gaps and questions, and areas we need to observe and understand better. That’s why it’s so important to do the exercise, and not just imagine we did it.

There's so much more to draw out from just this simple exercise. And seeing what others do with the exercise surfaces more; Jennifer Davis draws this out in a delightful and insightful post:

"We assume we know how the parts connect. We assume we know what the user needs. But when we are forced to draw it out, we see the gaps.

- I saw the mechanical structure.

- Brian saw the human relationship.

- Frankie saw the potential features.

None of us were wrong, but none of us had the full picture alone. To build better systems, we have to stop assuming our mental model is the only one that matters. We have to pick up a pencil, draw, share our drawing, and then see what everyone else is drawing."

The next step is integrating what we learn, and Dawn Ahukanna did just that!

“Powers of observation can be developed by cultivating the habit of watching things with an active, enquiring mind.” – WIB Beveridge

And a pencil.